Prismatic Category Theory

Posted by Tom Leinster

Guest post by C.B. Aberlé and Rubén Maldonado

Fibrations are a fundamental concept of category theory and categorical logic that have become increasingly relevant to the world of applied category theory thanks to their prominent use in applications such as the categorical semantics of dependent type theory, the study of dynamical systems, etc. With the increasing occurrence of higher-categorical structures in these applications, there is an evident need for both pure and applied category theorists to develop and refine higher-categorical analogues of the ordinary theory of fibrations.

This blog post aims to sketch the basis of a general framework for the study of higher-categorical fibrations. We begin with a recap of the fundamental building-blocks of the theory of Grothendieck fibrations, including Cartesian arrows and the Grothendieck construction. In doing so, we develop a simple graphical framework for studying properties of functors. An analysis of this framework then reveals that it can be interpreted in the internal language of the topos of simplicial sets, which paves the way for studying fibrations on higher-categorical structures such as double categories.

Fibres: from functions to functors

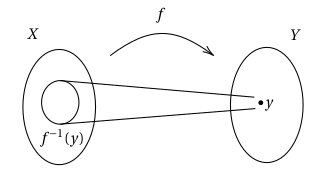

By way of motivating example, we begin with a comparison of notions of fibre for functions between sets and functors between categories, respectively. Recall that, for any function and , the fibre of is the subset , as in the following picture:

It follows straightforwardly that , i.e. is equal to the disjoint union of the fibres of . Hence we can always recover the domain of a function from its fibres.

There is an analogous notion of fibre for functors. Let be a functor, and consider an object . The fibre of over is defined to be the subcategory of consisting of all objects such that , and all morphisms such that .

Can we similarly recover the domain of a functor from its fibres, just as we could for functions? As it turns out, we can in general recover the objects of from the fibres of , but not necessarily the morphisms of , since some morphisms may not belong to any fibre.

This naturally prompts the question: what additional structure is needed on in order to be able to recover from its fibres? The answer to this question lies in the notion of a Grothendieck fibration.

Fibrations, Graphically

From Functors to Prisms

We begin by developing a graphical framework for representing the structure of a functor , based upon that of Sterling and Angiuli. Given objects and such that , we may think of as an object living in the fibre of over

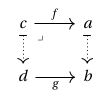

and we depict this arrangement as a dashed vertical arrow from to :

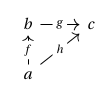

Similarly, given morphisms and such that , , and , we think of as lying over

and depict this as a square between the two dashed arrows corresponding to and , respectively:

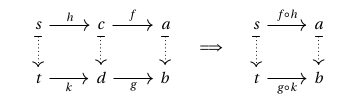

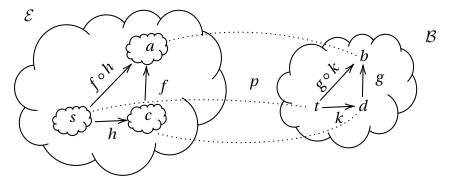

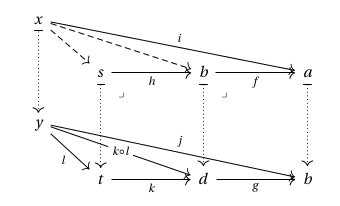

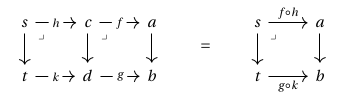

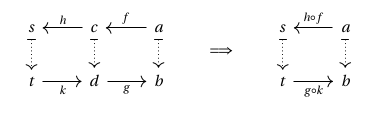

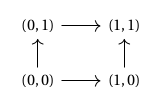

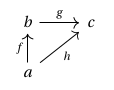

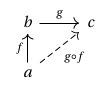

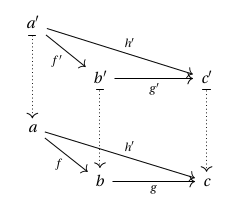

Squares of this form can be composed horizontally:

In fact, this is just another way of saying that preserves composition of morphisms, as in the following picture:

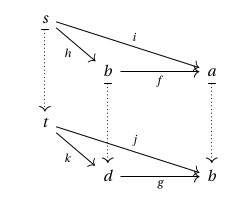

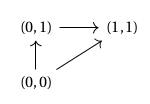

Given two such squares that horizontally compose to a third, these naturally arrange themselves into a triangular prism:

More generally, since must preserve all commuting diagrams in , for any diagram in living over one in , there is a corresponding depiction of this as a prism – e.g. a commuting square in over one in gives a cube:

Cartesian Arrows

Definition. A morphism lying over

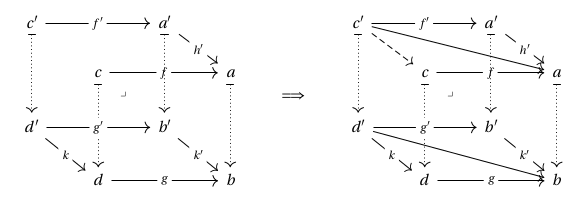

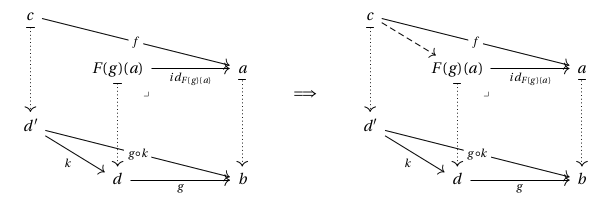

is called Cartesian if any partial prism as below can be uniquely completed to a prism:

In this case, we suggestively write

to indicate that the arrow is Cartesian.

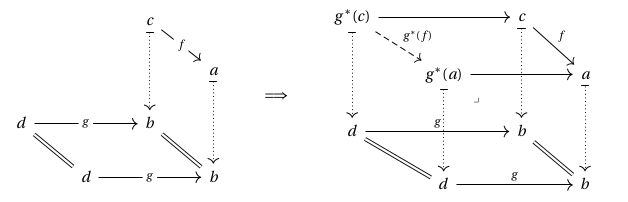

More generally, for a Cartesian arrow as above, any partial prism missing an incoming morphism to may be uniquely completed to a corresponding prism, since every commuting diagram may be decomposed into commuting triangles. E.g. any partial cube as below may be uniquely completed to a cube as follows:

The analogy of Cartesian squares to pullbacks is no accident – a Cartesian arrow as above may be informally viewed as a “limit” of the following diagram:

Following Johnson and Yau, we refer to a diagram of the former shape as a pre-lift, and to a Cartesian arrow completing the square as above as a Cartesian lift.

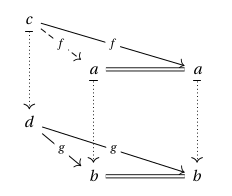

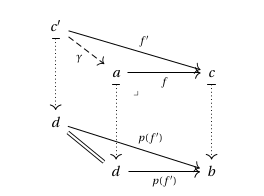

Like ordinary limits, Cartesian lifts are unique up to isomorphism, as shown in the following diagram:

Similarly, the composition of two Cartesian lifts is again Cartesian, since we have

Example. For any functor , every identity in is Cartesian:

Example. For any category , let be the arrow category of , i.e. the category whose objects are arrows in and whose morphisms are commuting squares. Let be the functor that sends an arrow to its codomain. Then a Cartesian arrow for is a pullback in .

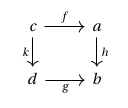

To see as much, note that in the graphical representation of the dashed arrows correspond to actual arrows, so e.g.~a square over is a commuting square

Such a square is Cartesian if any diagram as below can be uniquely completed to a prism:

which is equivalent to the universal property of a pullback.

Definition. A functor is a Grothendieck fibration (or fibration for short) if every pre-lift has a Cartesian lift. Much like ordinary limits, although Cartesian lifts are unique up to isomorphism, there may in fact be many possible choices of such lifts. A cloven fibration is a fibration equipped with a specific choice, for each pre-lift, of a corresponding Cartesian lift. A cloven fibration is called split if:

for every object , the chosen lift of and is

for every pair of composable morphisms, the chosen lift of and is equal to the composite of the chosen lift of and the chosen lift of .

Example. If is a discrete category (i.e. every morphism is an identity) then any functor is a fibration, since, as we have already seen, the Cartesian lift of any identity in is an identity in .

In particular, since sets are equivalently discrete categories, and functions between sets are equivalently functors between discrete categories, it follows that every function between sets (viewed as discrete categories) is a fibration. So in our initial motivating example concerning fibres of functions, we were in fact already implicitly working with fibrations.

Example. A category for which is a fibration is equivalently a category with all pullbacks. is moreover a split fibration if and only if the operation of taking successive pullbacks is strictly (unital and) associative, i.e.

This is particularly relevant when interpreting pullbacks as a kind of substitution, as in e.g. the categorical semantics of dependent type theory.

Lemma. Let be a fibration and let be any morphism in . It follows that factors as where is the Cartesian lift of and is in the fibre of .

Hence every morphism in factors as a composite of a Cartesian arrow, and an arrow in the fibre of an object in . Intuitively, Cartesian lifts “connect” the fibres of to one another. In fact, we can make this idea precise, by the following observation:

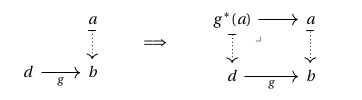

Observation. In a Grothendieck fibration, every morphism determines a functor , defined on objects as follows:

and on morphisms as follows:

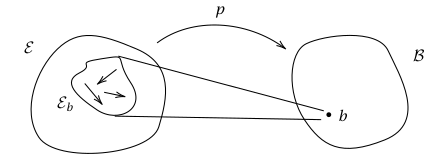

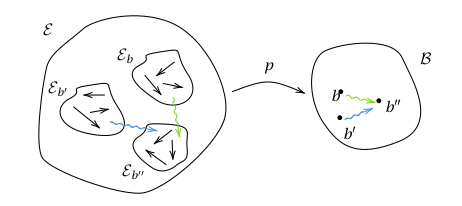

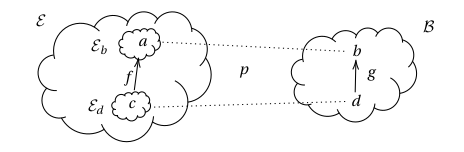

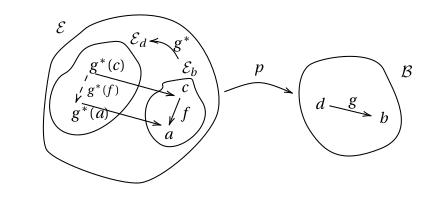

Hence in a fibration , the morphisms in provide a way to “travel” from one fibre to another, as in the following picture:

This structure of functors between fibres determines a pseudofunctor that maps an object to ; and maps a morphism in to .

The above answers our original motivating question of how to recover the morphisms of from the structure of the fibres of . In fact, we can go even further and construct (a category isomorphic to) out of the fibres of by “gluing” them together along the functors induced by morphisms in . This is precisely what the Grothendieck construction accomplishes.

The Grothendieck Construction

A principal raison d’être behind fibrations is to simplify the process of working with indexed categories. Given a base category , a -indexed category is a family of categories indexed by objects , such that morphisms contravariantly induce a functors , in a manner which preserves identities and composition of morphisms in up to coherent isomorphism. Equivalently, a -indexed category is a pseudofunctor .

We have just seen how every fibration gives rise to a -indexed category structure on its fibres. In fact, as we shall see, indexed categories are equivalent to fibrations. The key construct behind this equivalence is the Grothendieck construction, which can be viewed more generally as a way of reconstructing a functor from its graphical representation as described above. To make this idea precise, we make use of the notion of displayed categories – introduced by Ahrens and Lumsdaine – as a common generalization of indexed categories and the graphical representation of functors given above.

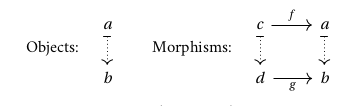

Definition. Given a base category , a displayed category over is a formal description of the graphical structure of a functor with codomain , consisting of:

For each object , a set of vertical arrows

for each morphism with vertical arrows into and into , a set of squares

together with identity squares and an operation of horizontal composition of squares that is unital and associative.

By definition, for any -displayed category , taking vertical arrows of as objects, and squares between these as morphisms, defines a category – the Grothendieck Construction of

Straightforwardly, there is a functor , which sends each vertical arrow/square in to the object/morphism in over which it lies. This construction of realizes as a functor into , such that the graphical representation of is precisely .

Conversely, given a functor , the Grothendieck construction of its corresponding displayed category yields a functor such that there is an isomorphism of categories that commutes with and .

Hence functors are equivalent to displayed categories, via the Grothendieck construction, and we have already seen how every fibration gives rise to an indexed category. To show that the Grothendieck construction descends to an equivalence between fibrations and indexed categories, it thus suffices to show that every indexed category corresponds to a displayed category with the universal property of a fibration.

From pseudofunctors to fibrations: Let be a pseudofunctor. We define a displayed category over as follows:

For each object , an object lying over is an object of .

For each morphism , for objects and , a morphism from to over is a morphism where is the functorial action of on .

For each object with , the identity square is given by , and the composition of and is given by

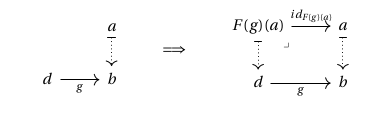

Moreover, has the universal property of a fibration, since for any pre-lift consisting of and as below, we may take the Cartesian lift to be the object , along with the identity :

which is indeed Cartesian, since any diagram as below can be uniquely completed to a triangular prism, by pseudofunctoriality:

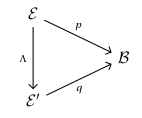

This correspondence between indexed categories and fibrations can be extended to a 2-equivalence between the 2-category of -indexed categories and the 2-category of fibrations over :

Theorem. There is a 2-equivalence .

We provide a brief description of these 2-categories and how acts on cells in the following subsections.

The 2-category of -indexed categories

In this subsection, we introduce the 2-category .

Definition. For any category , the 2-category denoted as consist of the following:

Objects. Pseudounctors .

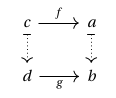

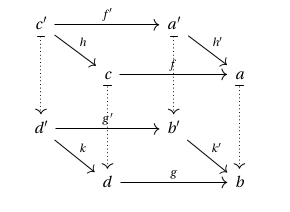

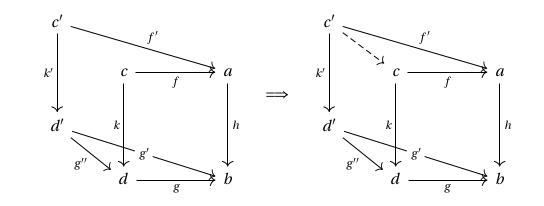

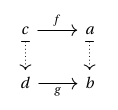

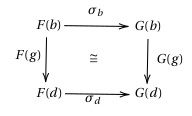

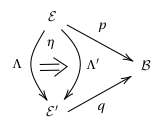

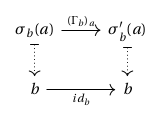

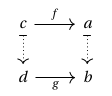

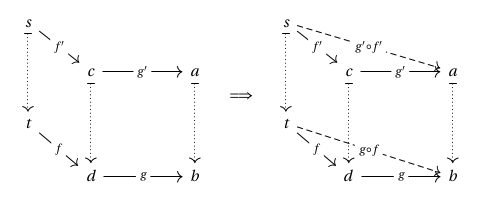

1-cells. Strong natural transformations. A strong natural transformation consists of a collection of functors indexed by object . For every morphism in , the following diagram must commute up to coherent isomorphism:

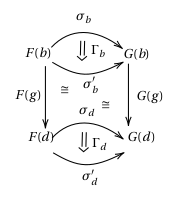

2-cells. Modifications. A modification between two strong natural transformations is a collection of natural transformations for every , such that for any in , the following whiskering diagram commutes:

The 2-category of fibrations

Definition. For any category , the 2-category denoted as consists of the following:

Objects. Fibrations .

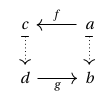

1-cells. The 1-cells between two fibrations and are cartesian functors. Those are functors that make the diagram commute

and send cartesian arrows to cartesian arrows.

2-cells. The 2-cells are vertical natural transformations, which is to say: natural transformations between cartesian functors and that make the following whiskering diagram commute:

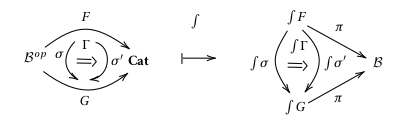

In the first part of this section, we described how to construct a fibration from a pseudofunctor . Finally, in order to better understand the 2-equivalence , we define its action on 1-cells and 2-cells:

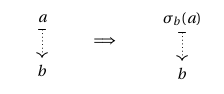

Definition. Let and be objects in , and let be a natural transformation. The cartesian functor :

maps objects according to

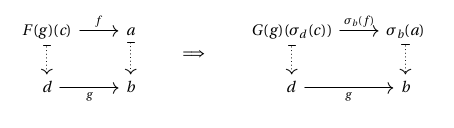

similarly, it maps morphisms according to

Definition. Let be a modification. The vertical natural transformation is defined for every pair in as the morphism

Example. Given an indexed category , its fibrewise opposite is the pseudofunctor that maps to .

Passing from this to the functor via the Grothendieck construction, the objects of each fibre of are the same as those of , but now for any morphism , a morphism lying over this in goes in the opposite direction as . We may depict this graphically as a “twisted” square:

and we refer to squares of this form as “lenses”. Lenses compose horizontally, but note now how composition upstairs goes in the opposite direction as downstairs:

The category obtained from this construction is called the category of lenses of , and is of central importance in the emerging field of categorical systems theory. The essential idea behind the use of lenses in categorical systems theory is that lenses provide a good model of bidirectional processes – i.e. processes that interact with one another by both sending information (along the lower – “forward” – map) and receiving information (along the upper – “backward” – map).

Myers has shown how this definition of lenses gives rise to a certain kind of doubly-indexed category, whose structure allows one to study the compositional properties of behaviors of dynamical systems. Such a doubly-indexed category should correspond, via a double-categorical analogue of the Grothendieck construction, to a particular double fibration.

To better understand constructions of this sort, and their applications in categorical systems theory and beyond, we are interested in developing methods of working with such higher-categorical structures that allow us to manage the oft-complicated coherence conditions that arise thereabouts. For this purpose, it is useful to work synthetically with such structures – i.e. by working in the internal language of some well-structured category in which these structures naturally reside. As it happens, we have already been implicitly using such a synthetic approach in our discussion of fibrations up to this point, which we now specify more precisely.

Fibrations, Synthetically

In our previous – prismatic – study of fibrations, we saw how the property of being a Cartesian arrow for a functor/displayed category could be reduced to that of every commuting triangle in the base category with a specified boundary lifting uniquely to a filling for the corresponding triangular prism. This suggests that a synthetic framework for reasoning about shapes such as triangles, prisms, etc., ought to be a good setting in which to study the sorts of constructions we have encountered in previous sections.

A suitable category whose internal language allows us to represent and reason about such shapes is the category of simplicial sets . There are several properties of that make it a good setting for the synthetic study of (higher) categories, fibrations, etc. In particular, it is a (presheaf) topos, which for our purposes means that its internal language supports all the usual constructs of dependent type theory, specifically:

Types , containing elements .

Subtypes, where is the type containing all elements that satisfy .

Dependent types, where a family of types dependent upon is such that is a type for each .

Dependent function types, where is the type of functions such that for all . In the case where does not depend upon , this reduces to the usual function type .

Dependent pair types, where is the type of pairs such that and . In the case where does not depend upon , this reduces to the usual product type .

A key property of the internal type-theoretic language of (as developed in the more general setting of simplicial spaces by Riehl and Shulman) is that it includes a special type , corresponding to the standard 1-simplex, equipped with the following additional structure:

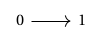

There are two distinguished elements

is totally ordered by a binary relation for which is the least element and is the greatest element.

(For those who know a bit of topos theory, this is due to the fact that is the classifying topos of bounded total orders). We think of as representing an abstract line segment or path with and as designated endpoints, as follows:

Using the language of dependent type theory, we can then build more complex shapes out of such paths. In particular, the Cartesian product of two line segments – i.e. – is a square, i.e.

while a triangle may be represented as the portion of such a square lying above the diagonal:

corresponding to the following subtype of the square : More generally, the standard -simplex may be defined as the type as these are in fact equivalent to the Yoneda embeddings in of the standard simplices in the simplex category .

We may then use these abstract shapes to detect corresponding structure in other types by mapping into them. E.g. a path from to in a type is a function such that and , and we write for the type of such paths, and depict them the same as morphisms in categories, using directed arrows, i.e.

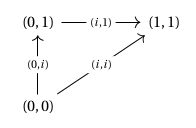

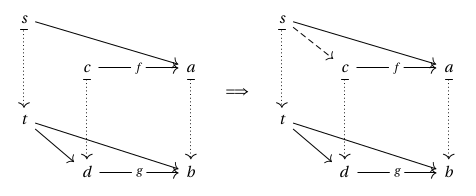

In particular, there are three non-trivial (i.e. non-constant) functions , namely the functions that map to , and , respectively, which together pick out the three paths on the boundary of as follows:

Hence given a type with and and and , a triangle in with boundary given by as depicted below

is a function such that , , and for all .

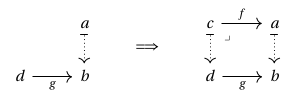

In order to recover ordinary category theory in this setting, we should have some way of viewing the language of categories as somehow embedded in that of simplicial sets. For a given type in the language of simplicial sets, a triangle

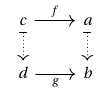

in may be thought of as a witness to the fact that is a valid solution to the problem of composing and . A category is then just a type where – in the internal language of – every such “composition problem” has a unique solution, i.e. for any with and , there is a unique completion of this to a triangle as follows:

One straightforwardly verifies that the uniqueness of such solutions implies the associativity of composition, since for any composable sequence of paths , a solution to the composition problem for the triangle formed by and is also a solution to the composition problem for and , and vice versa, so these two solutions must be identical. Unitality of composition follows by similar reasoning.

Hence, in the language of simplicial sets, being a category is only a property of a type. In fact, this definition of categories is equivalent to the embedding given by the nerve functor. In particular, any function , where are both categories in the above sense, is automatically a functor in the usual sense, since any path in is taken to a path in , and similarly for triangles, hence preserves composition, etc. We can thus suppress much of the bookkeeping to do with checking functoriality conditions, etc., by treating categories as a special kind of simplicial sets, and working in the internal language of the latter.

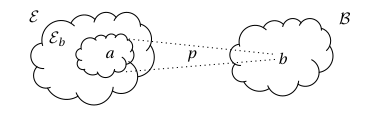

This simplification is especially apparent when we consider the interpretation of our prior treatment of displayed categories and the Grothendieck construction in this framework. Given a family of types dependent upon , we may think of an element for as living over in the structure of , and represent this using our dashed vertical arrow notation from before:

Then for with and and a path , we may define a path from to lying over as a dependent function such that and . We may depict this just as we did in the case of functors/displayed categories as a square, i.e.:

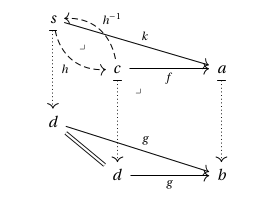

And similarly, for such a family of types dependent upon , given a triangle with boundary in , and paths lying over these, respectively, a prism as depicted in the following diagram

corresponds to a dependent function such that , and for all .

Given such a type family dependent upon , the Grothendieck construction of may be interpreted in as the dependent pair type whose elements are pairs with and .

That a path in is equivalently a square consisting of and follows from the distributivity of function types over pair types, i.e.

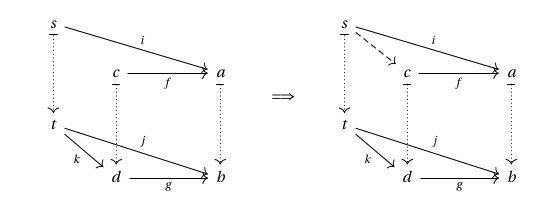

If is a category in , then a type family dependent upon is a displayed category if every partial prism has a unique completion as follows:

And just as before, a dependent path lying over is Cartesian iff every partial prism has a unique completion as follows:

Hence we can interpret all of our previous definitions and constructions regarding fibrations, the Grothendieck construction, etc., into this simplicial framework, by simply translating the shapes occurring in these constructions into corresponding types and functions in the internal language of simplicial sets.

As a final illustration of this, we now sketch how this technique may be used to give economical definitions of both double categories and double fibrations.

A Recipe for Double-Categorical Structure

In the above, we have defined categories in one way as certain types in the internal language of . But since this internal language supports all the usual constructs of dependent type theory, we can just as well define category objects internally in simplicial set in the usual way, i.e. as a type of objects and a type family dependent upon together with an associative and unital composition operation and identities.

Recall that a (strict) double category is equivalently a category object internal to . Since the definition of an internal category object makes use only of (finite) limits, which are preserved by the nerve functor (since it is a right adjoint), it follows that an internal category object in whose component types are all nerves of categories is equivalently a strict double category.

Hence again in the language of simplicial sets, we can reduce being a double category to a mere property of an internal category object (namely the property that its types of objects and morphisms are themselves nerves of categories). Moreover, an (internal) functor between such categories is then automatically a double functor.

Finally, we note that such a double functor, viewed as an ordinary functor in the language of simplicial sets, may be considered a fibration in two distinct ways: either by requiring that it satisfy the ordinary property of a Grothendieck fibration – as a functor between internal categories – or that each of its component functions (i.e. those mapping objects/morphisms of the domain to those of the codomain) themselves be fibrations in the simplicial sense defined above. We conjecture that requiring both of these properties to hold is equivalent (in the strict case) to the definition of double fibrations given by Cruttwell, Lambert, Pronk and Szyld, wherein they define a double fibration as an internal category in the 2-category of fibrations over arbitrary bases. We hope to further explore this connection and perhaps prove this conjecture during the upcoming research week for the Adjoint School!

Much remains to be done in fleshing out the theory of double fibrations. We hope that the above-described framework may be a valuable tool for this direction of study. In particular, we are interested to know how much of the ordinary theory of fibrations translates to double fibrations, and we hope that this framework can unify and simplify the task of answering these questions, by translating ordinary categorical definitions into the internal language of simplicial sets, and seeing how these interact with properties arising from nerves of categories. Because of its type-theoretic flavor, it should moreover be possible to formalize this treatment of (double) fibrations in a proof assistant such as Agda or Lean. All these and other applications we hope to explore further during the Adjoint School research week. For now, we hope to have sufficiently demonstrated the utility and simplifying power of the simplicial approach to fibrations in both pure and applied category theory.

Re: Prismatic Category Theory

Just a PSA that this is not obviously connected with prismatic cohomology, in case anyone was expecting that.