The Brunn-Minkowski Inequality

Posted by Tom Leinster

Let and be measurable subsets of . Then

where . This is the Brunn-Minkoswki inequality. It’s most often mentioned in the case where and are convex, but it’s true in the vast generality of measurable sets (except for , where it obviously fails).

Here I want to explain just a few basic things about this inequality and its consequences. For instance, it easily implies the famous isoperimetric inequality: that among all sets with a given surface area, the one that maximizes the volume is the ball.

There’s a fantastic expository paper that covers everything I’m about to say and much, much more:

Richard Gardner, The Brunn-Minkowski inequality. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 39 (2002), 355-405.

Thanks to Mark Meckes for mentioning this paper to me years ago. Cognoscenti like him may prefer this earlier, longer version. Both versions contain, among other things, a nice short proof of the inequality (Section 4 of the published version and Section 6 of the longer version). But I won’t give the proof here, nor will I mention the conditions for equality to hold.

The term is known as a Minkowski sum. You can think of as smeared out in a pattern dictated by :

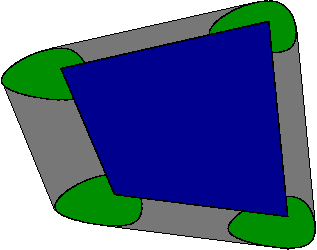

For instance, if is an egg shape (green) and is a quadrilateral (blue) then looks like the entire shape here:

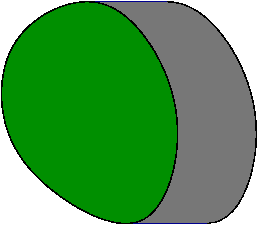

(When I wrote those words, I didn’t mean to invoke the mental image of smearing an egg around a table. But maybe it’s not such a bad image to have.) Or again, if is egg-like and is a line segment then looks like this:

Of course, there’s also a complementary viewpoint: is smeared out in a pattern dictated by :

In any case, an important observation is that

can have large volume even if and both have volume zero.

For instance, this happens in the plane when is a horizontal line segment and is a vertical line segment. There’s obviously no hope of getting an equation for in terms of and . But this example suggests that we might be able to get an inequality, stating that is at least as big as some function of and .

The Brunn-Minkowski inequality does this, but it’s really about linearized volume, , rather than volume itself. If length is measured in metres then so is . There’s also a much cruder corollary of Brunn-Minkowski that concerns actual volume. Take the Brunn-Minkowski inequality

and raise each side to the power of . The right-hand side can be expanded using the binomial theorem, and throwing away all except the first and last terms gives

as a corollary of Brunn-Minkowski.

This is a much weaker statement than the Brunn-Minkowski inequality, because in deriving it we threw away a huge number of positive terms. But it’s interesting in its own right, and has an easy direct proof. Here’s an argument I was told by Joe Fu. I’ll indent it for easy skippability.

Let and be measurable subsets of , and assume they’re both bounded. (Once we’ve proved the bounded case, it’s not hard to deduced the general case, but I’ll leave that as a puzzle.) We’re going to prove that contains almost-disjoint translates of and of , where by “almost disjoint” I mean that their intersection has measure zero. The inequality will follow.

The idea is that we shift as high as possible and as low as possible. Formally, define by as . (That’s for “height”, but any other nonzero linear functional would work just as well.) Choose maximizing and minimizing . It’s enough to show that

is a subset of a hyperplane, since then it has measure zero. So, let be any point in this intersection. We can write for some , and so

But we can also write for some , and a similar argument gives . So we’ve shown that every belongs to the hyperplane , and that completes the proof.

That was a very weak consequence of the Brunn-Minkowski inequality, but here’s a more powerful and interesting one. In a slogan:

Brunn-Minkowski for small balls is the isoperimetric inequality.

In other words, if you take any , and take to be a ball of radius tending to zero, then the Brunn-Minkowski inequality becomes the isoperimetric inequality in .

To explain this, I first need to explain what the isoperimetric inequality is. The word “isoperimetric” suggests the two-dimensional version: that among all subsets of with a prescribed perimeter, the one with the greatest area is the disc. But I mean the general -dimensional version, which I’ll now state.

Every reasonable subset has a volume (its Lebesgue measure), which I’ll write now as . It also has a surface area, which I’ll write as . The isoperimetric inequality states that for nice enough subsets (and I’ll come back to what that means),

where the radius is chosen so that

We can easily solve for in this last equation, using the fact that is homogeneous of degree . After a little bit of elementary algebraic rearranging, we find an equivalent form of the isoperimetric inequality that doesn’t have an “” in it:

for all .

This can be understood as follows.

Loosely speaking, the isoperimetric inequality says that the ratio of a shape’s volume to its surface area is greatest for balls. But we shouldn’t take the word “ratio” literally: for if we simply divided volume by surface area then we’d get a quantity measured in metres, so we could make it bigger simply by scaling the set up! What we want this ratio to be is a dimensionless quantity.

Since volume is measured in metres and surface area is measured in metres, we can get a dimensionless quantity by linearizing both things before we take the ratio. In other words, take the th root of the volume and the th root of surface area, so that both are measured in metres. Then the ratio will come out to be dimensionless.

(If you’re feeling perverse, you could instead take the th power of the volume and the th power of the surface area, then divide one by the other. This would be a dimensionless quantity. But since it’s just the 17th power of the ratio in the last paragraph, and taking the 17th power is an order-preserving operation, it wouldn’t change the meaning of the inequality.)

To get much further, we need to ask: what is surface area? The usual idea is that the volume of a thin shell around , of thickness , should be approximately times the surface area. So, we define

where means the set of all points within distance of . Since we’re talking about Minkowski sums, it’s useful to observe that

where means the -dimensional unit ball.

I confess that I don’t know exactly when the limit above exists; I guess there are measurable sets for which it doesn’t. And among those sets for which the limit does exist, I don’t know when it’s the right definition of surface area. But certainly everything works as it should when is convex and compact, since then is actually a polynomial in whose linear term is the surface area. (That’s part of Steiner’s theorem.) So let’s just assume that is convex and compact.

Now we’ll use this formula to calculate the surface area of the unit ball. Taking ,

using the fact that is homogeneous of degree . So,

For instance, in , the volume of the unit ball is and the surface area of the unit sphere is .

Back to Brunn-Minkowski! I promised to show you that the isoperimetric inequality is just the Brunn-Minkowski inequality in the case where one of the two sets involved is a small ball. We’ve put the isoperimetric inequality into a form where it involves th powers, which also appear in the Brunn-Minkowski inequality. So things are looking promising… Here goes.

Take (definitely measurable, probably convex and compact). The Brunn-Minkowski inequality tells us that for all ,

Rearranging, this is equivalent to

Now let . The left-hand side is just the definition of . The right-hand side is recognizable as a derivative, give or take a constant factor. So the Brunn-Minkowski inequality for (vanishingly) small balls states that for nice enough ,

This looks like a mess until we remember the formula for the surface area of the unit ball: . Using this to get rid of the in the inequality, and doing one last bit of elementary rearrangement, we get

And that’s exactly the isoperimetric inequality.

Re: The Brunn-Minkowski Inequality

Nice post, Tom. To readers whose background isn’t in certain areas of geometry and analysis, it’s not obvious that the Brunn–Minkowski inequality is more than a curiosity, the proof of the isoperimetric inequality notwithstanding. So let me add that Brunn–Minkowski is an absolutely vital tool in many parts of geometry, analysis, and probability theory, with extremely diverse applications. Gardner’s survey is a great place to start, but by no means exhaustive.

I’ll also add a couple remarks about regularity issues. You point out that Brunn–Minkowski holds “in the vast generality of measurable sets”, but it may not be initially obvious that this needs to be interpreted as “when , , and are all Lebesgue measurable”, since need not be measurable when and are (although you can modify the definition of to work for arbitrary measurable and ; this is discussed by Gardner).

You raised the question of when the limit defining exists. As you note, it does exist for compact convex sets. It also holds if is compact with piecewise boundary (see the appendix here). More generally, if you replace the limit with a lim inf, you get something called the Minkowski–Steiner formula. The standard reference for when this turns out to be the “right” notion of surface area is Federer’s famously impenetrable book. I believe that all this is related to “sets with positive reach”. I don’t know anything about those, but I know that Joe Fu does, so if I wanted to learn about them I’d ask him where to start.