Martianus Capella

Posted by John Baez

I’ve been blogging a bit about medieval math, physics and astronomy over on Azimuth. I’ve been writing about medieval attempts to improve Aristotle’s theory that velocity is proportional to force, understand objects moving at constant acceleration, and predict the conjunctions of Jupiter and Saturn. A lot of interesting stuff was happening back then!

As a digression from our usual fare on the -Café, here’s one of my favorites, about an early theory of the Solar System, neither geocentric nor heliocentric, that became popular thanks to a quirk of history around the time of Charlemagne. The more I researched this, the more I wanted to know.

In 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus published a book arguing that the Earth revolves around the Sun: De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.

This is sometimes painted as a sudden triumph of rationality over the foolish yet long-standing belief that the Sun and all the planets revolve around the Earth. As usual, this triumphalist narrative is oversimplified. In the history of science, everything is always more complicated than you think.

First, Aristarchus had come up with a heliocentric theory way back around 250 BC. While Copernicus probably didn’t know all the details, he did know that Aristarchus said the Earth moves. Copernicus mentioned this in an early unpublished version of De revolutionibus.

Copernicus also had some precursors in the Middle Ages, though it’s not clear whether he was influenced by them.

In the 1300’s, the philosopher Jean Buridan argued that the Earth might not be at the center of the Universe, and that it might be rotating. He claimed — correctly in the first case, and only a bit incorrectly in the second — that there’s no real way to tell. But he pointed out that it makes more sense to have the Earth rotating than have the Sun, Moon, planets and stars all revolving around it, because

it is easier to move a small thing than a large one.

In 1377 Nicole Oresme continued this line of thought, making the same points in great detail, only to conclude by saying

Yet everyone holds, and I think myself, that the heavens do move and not the Earth, for “God created the orb of the Earth, which will not be moved” [Psalms 104:5], notwithstanding the arguments to the contrary.

Everyone seems to take this last-minute reversal of views at face value, but I have trouble believing he really meant it. Maybe he wanted to play it safe with the Church. I think I detect a wry sense of humor, too.

Martianus Capella

I recently discovered another fascinating precursor of Copernicus’ heliocentric theory: a theory that is neither completely geocentric nor completely heliocentric! And that’s what I want to talk about today.

Sometime between 410 and 420 AD, Martianus Capella came out with a book saying Mercury and Venus orbit the Sun, while the other planets orbit the Earth!

This picture is from a much later book by the German astronomer Valentin Naboth, in 1573. But it illustrates Capella’s theory — and as we’ll see, his theory was rather well-known in western Europe starting in the 800s.

First of all, take a minute to think about how reasonable this theory is. Mercury and Venus are the two planets closer to the Sun than we are. So, unlike the other planets, we can never possibly see them more than 90° away from the Sun. In fact Venus never gets more than 48° from the Sun, and Mercury stays even closer. So it looks like these planets are orbiting the Sun, not the Earth!

But who was this guy, and why did he matter?

Martianus Capella was a jurist and writer who lived in the city of Madauros, which is now in Algeria, but in his day was in Numidia, one of six African provinces of the Roman Empire. He’s famous for a book with the wacky title De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii, which means On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury. It was an allegorical story, in prose and verse, describing the courtship and wedding of Mercury (who stood for “intelligent or profitable pursuit”) and the maiden Philologia (who stood for “the love of letters and study”). Among the wedding gifts are seven maids who will be Philology’s servants. They are the seven liberal arts:

- The Trivium: Grammar, Dialectic, Rhetoric.

- The Quadrivium: Geometry, Arithmetic, Astronomy, Harmony.

In seven chapters, the seven maids explain these subjects. What matters for us is the chapter on astronomy, which explains the structure of the Solar System.

This book De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii became very important after the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, mainly as a guide to the liberal arts. In fact, if you went to a college that claimed to offer a liberal arts education, you were indirectly affected by this book!

Here is a painting by Botticelli from about 1485, called A Young Man Being Introduced to the Seven Liberal Arts:

The Carolingian Renaissance

But why did Martianus Capella’s book become so important?

I’m no expert on this, but it seems as the Roman Empire declined there was a gradual dumbing down of scholarship, with original and profound works by folks like Aristotle, Euclid, and Ptolemy eventually being lost in western Europe — though preserved in more civilized parts of the world, like Baghdad and the Byzantine Empire. In the west, eventually all that was left were easy-to-read popularizations by people like Pliny the Elder, Boethius, Macrobius, Cassiodorus… and Martianus Capella!

By the end of the 800s, many copies of Capella’s book De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii were available. Let’s see how that happened!

To set the stage: Charlemagne became King of the Franks in 768 AD. Being a forward-looking fellow, he brought in Alcuin, headmaster of the cathedral school in York and “the most learned man anywhere to be found”, to help organize education in his kingdom.

Alcuin set up schools for boys and girls, systematized the curriculum, raised the standards of scholarship, and encouraged the study of liberal arts. Yes: the liberal arts as described by Martianus Capella! For Alcuin this was all in the service of Christianity. But scholars, being scholars, took advantage of this opportunity to start copying the ancient books that were available, writing commentaries on them, and the like.

In 800, Charlemagne became emperor of what’s now called the Carolingian Empire. When Charlemagne died in 814 a war broke out, but it ended in 847. Though divided into three parts, the empire flourished until about 877, when it began sinking due to internal struggles, attacks from Vikings in the north, etc.

The heyday of culture in the Carolingian Empire, roughly 768–877, is sometimes called the Carolingian Renaissance because of the flourishing of culture and learning brought about by Alcuin and his successors. To get a sense of this: between 550 and 750 AD, only 265 books have been preserved from Western Europe. From the Carolingian Renaissance we have over 7000.

However, there was still a huge deficit of the classical texts we now consider most important. As far as I can tell, the works of Aristotle, Eratosthenes, Euclid, Ptolemy and Archimedes were completely missing in the Carolingian Empire. I seem to recall that from Plato only the Timaeus was available at this time. But Martianus Capella’s De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii was very popular. Hundreds of copies were made, and many survive even to this day! Thus, his theory of the Solar System, where Mercury and Venus orbited the Sun but other planets orbited the Earth, must have had an out-sized impact on cosmology at this time.

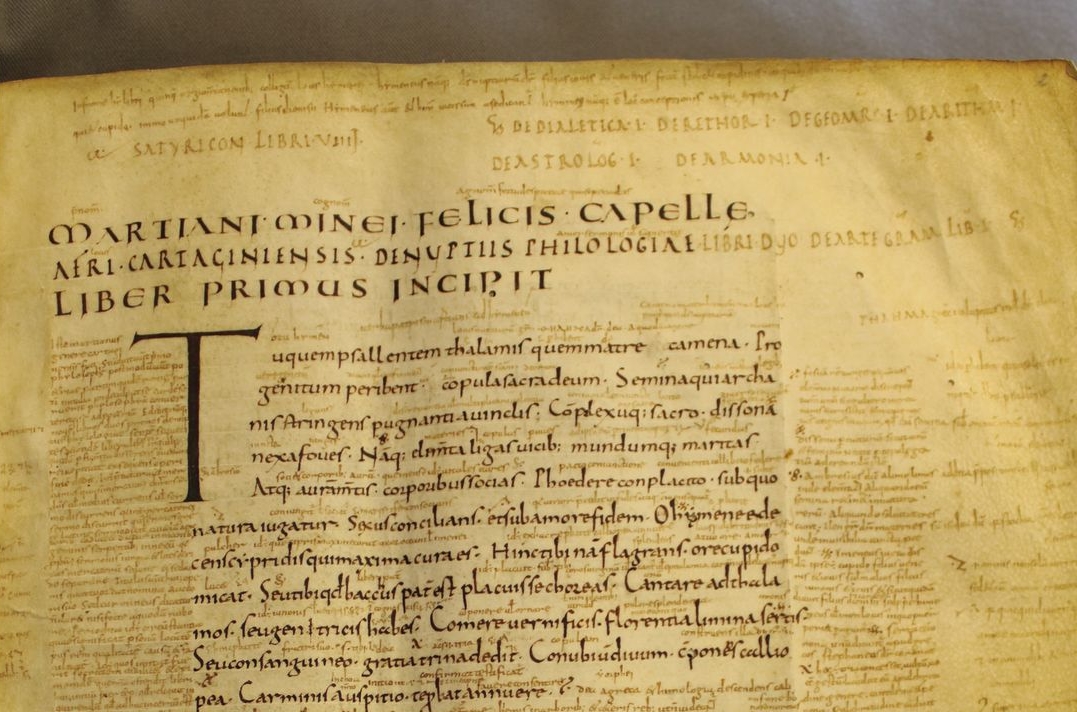

Here is part of a page from one of the first known copies of De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii:

It’s called VLF 48, and it’s now at the university library in Leiden. Most scholars say it dates to 850 AD, though Mariken Teeuwen has a paper claiming it goes back to 830 AD.

You’ll notice that in addition to the main text, there’s a lot of commentary in smaller letters! This may have been added later. Nobody knows who wrote it, or even whether it was a single person. It’s called the Anonymous Commentary. This commentary was copied into many of the later versions of the book, so it’s important.

The Anonymous Commentary

So far my tale has been a happy one: even in the time of Charlemagne, the heliocentric revolt against the geocentric cosmology was brewing, with a fascinating ‘mixed’ cosmology being rather well-known.

Alas, now I need to throw a wet blanket on that, and show how poorly Martianus Capella’s cosmology was understood at this time!

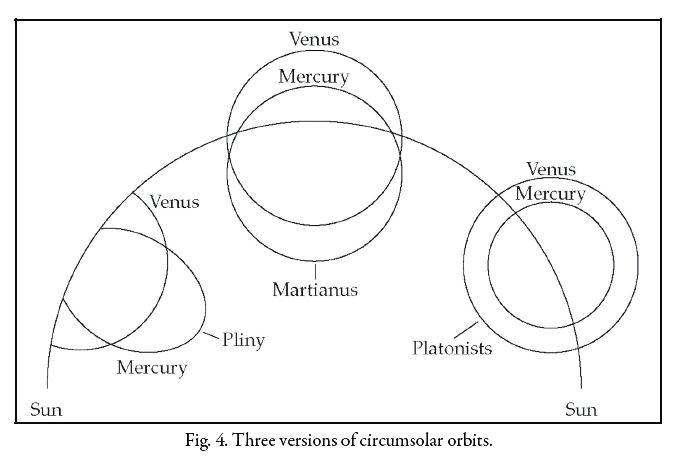

The Anonymous Commentary actually describes three variants of Capella’s theory of the orbits of Mercury and Venus. One of them is good, one seems bad, and one seems very bad. Yet subsequent commentators in the Carolingian Empire didn’t seem to recognize this fact and discard the bad ones.

These three variants were drawn as diagrams in the margin of VLF 48, but Robert Eastwood has nicely put them side by side here:

The one at right, which the commentary attributes to the “Platonists”, shows the orbit of Mercury around the Sun surrounded by the larger orbit of Venus. This is good.

The one in the middle, which the commentary attributes to Martianus Capella himself, shows the orbits of Mercury and Venus crossing each other. This seems bad.

The one at left, which the commentary attributes to Pliny, shows orbits for Mercury and Venus that are cut off when they meet the orbit of the Sun, not complete circles. This seems very bad — so bad that I can’t help but hope there’s some reasonable interpretation that I’m missing. (Maybe just that these planets get hidden when they go behind the Sun?)

Robert Eastwood attributes the two bad models to a purely textual approach to astronomy, where commentators tried to interpret texts and compare them to other texts, without doing observations. I’m still puzzled.

Copernicus

Luckily, we’ve already seen that by 1573, Valentin Naboth had settled on the good version of Capella’s cosmology:

That’s 30 years after Copernicus came out with his book… but the clarification probably happened earlier. And Copernicus did mention Martianus Capella’s work. In fact, he used it to argue for a heliocentric theory! In Chapter 10 of De Revolutionibus he wrote:

In my judgement, therefore, we should not in the least disregard what was familiar to Martianus Capella, the author of an encyclopedia, and to certain other Latin writers. For according to them, Venus and Mercury revolve around the sun as their center. This is the reason, in their opinion, why these planets diverge no farther from the sun than is permitted by the curvature of their revolutions. For they do not encircle the earth, like the other planets, but “have opposite circles”. Then what else do these authors mean but that the center of their spheres is near the sun? Thus Mercury’s sphere will surely be enclosed within Venus’, which by common consent is more than twice as big, and inside that wide region it will occupy a space adequate for itself. If anyone seizes this opportunity to link Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars also to that center, provided he understands their spheres to be so large that together with Venus and Mercury the earth too is enclosed inside and encircled, he will not be mistaken, as is shown by the regular pattern of their motions.

For [these outer planets] are always closest to the earth, as is well known, about the time of their evening rising, that is, when they are in opposition to the sun, with the earth between them and the sun. On the other hand, they are at their farthest from the earth at the time of their evening setting, when they become invisible in the vicinity of the sun, namely, when we have the sun between them and the earth. These facts are enough to show that their center belongs more to then sun, and is identical with the center around which Venus and Mercury likewise execute their revolutions.

Conclusion

What’s the punchline? For me, it’s that there was not a purely binary choice between geocentric and heliocentric cosmologies. Instead, many options were in play around the time of Copernicus:

In classic geocentrism, the Earth was non-rotating and everything revolved around it.

Buridan and Oresme strongly considered the possibility that the Earth rotated… but not, apparently, that it revolved around the Sun.

Capella believed Mercury and Venus revolved around the Sun… but the Sun revolved around the Earth.

Copernicus believed the Earth rotates, and also revolves around the Sun.

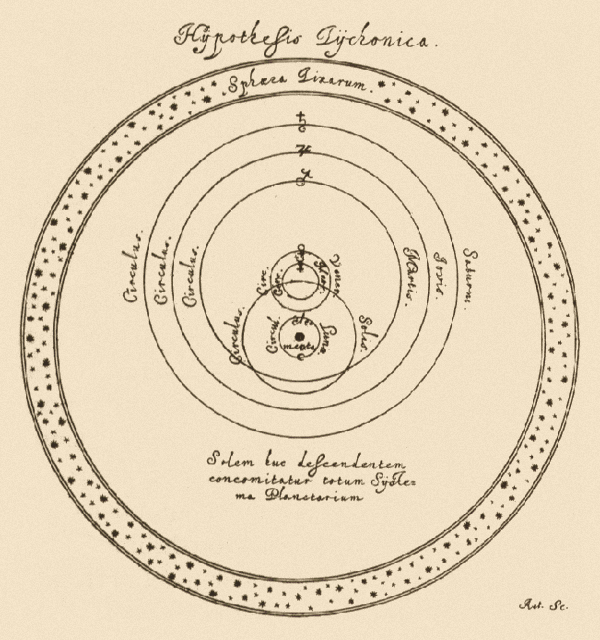

And to add to the menu, Tycho Brahe, coming after Copernicus, argued that all the planets except Earth revolve around the Sun, but the Sun and Moon revolve around the Earth, which is fixed.

And Capella’s theory actually helped Copernicus!

This diversity of theories is fascinating… even though everyone holds, and I think myself, that the Earth revolves around the Sun.

Above is a picture of the “Hypothesis Tychonica”, from a book written in 1643.

References

We know very little about Aristarchus’ heliocentric theory. Much comes from Archimedes, who wrote in his Sand-Reckoner that

You King Gelon are aware the ‘universe’ is the name given by most astronomers to the sphere the centre of which is the centre of the earth, while its radius is equal to the straight line between the centre of the sun and the centre of the earth. This is the common account as you have heard from astronomers. But Aristarchus has brought out a book consisting of certain hypotheses, wherein it appears, as a consequence of the assumptions made, that the universe is many times greater than the ‘universe’ just mentioned. His hypotheses are that the fixed stars and the sun remain unmoved, that the earth revolves about the sun on the circumference of a circle, the sun lying in the middle of the orbit, and that the sphere of fixed stars, situated about the same centre as the sun, is so great that the circle in which he supposes the earth to revolve bears such a proportion to the distance of the fixed stars as the centre of the sphere bears to its surface.

The last sentence, which Archimedes went on to criticize, seems to be a way of saying that the fixed stars are at an infinite distance from us.

For Aristarchus’ influence on Copernicus, see:

- Owen Gingerich, Did Copernicus owe a debt to Aristarchus?, Journal for the History of Astronomy 16 (1985), 37–42.

An unpublished early version of Copernicus’ De revolutionibus, preserved at the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków, contains this passage:

And if we should admit that the motion of the Sun and Moon could be demonstrated even if the Earth is fixed, then with respect to the other wandering bodies there is less agreement. It is credible that for these and similar causes (and not because of the reasons that Aristotle mentions and rejects), Philolaus believed in the mobility of the Earth and some even say that Aristarchus of Samos was of that opinion. But since such things could not be comprehended except by a keen intellect and continuing diligence, Plato does not conceal the fact that there were very few philosophers in that time who mastered the study of celestial motions.

For Buridan on the location and possible motion of the Earth, see:

- John Buridan, Questions on the Four Books on the Heavens and the World of Aristotle, Book II, Question 22, trans. Michael Claggett, in The Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin, 1961, pp. 594–599.

For Oresme on similar issues, see:

- Nicole Oresme, On the Book on the Heavens and the World of Aristotle, Book II, Chapter 25, trans. Michael Claggett, in The Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin, 1961, pp. 600–609.

Both believed in a principle of relativity for rotational motion, so they thought there’d be no way to tell whether the Earth was rotating. This of course got revisited in Newton’s rotating bucket argument, and then Mach’s principle, frame-dragging in general relativity, and so on.

You can read Martianus Capella’s book in English translation here:

William Harris Stahl, Evan Laurie Burge and Richard Johnson, eds., Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts: The Marriage of Philology and Mercury. Vol. 2., Columbia University Press, 1971.

I got my figures on numbers of books available in the early Middle Ages from here:

- Dusan Nikolic, What was the Carolingian Renaissance?, 2023 April 6.

This is the best source I’ve found on Martianus Capella’s impact on cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance:

- Bruce S. Eastwood, Ordering the Heavens: Roman Astronomy and Cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance, Brill, 2007.

This also good:

- Mariken Teeuwen and Sínead O’Sullivan, eds., Carolingian Scholarship and Martianus Capella: Ninth-Century Commentary Traditions on De nuptiis in Context, The Medieval Review (2012).

In this book, the essay most relevant to Capella’s cosmology is again by Eastwood:

- Bruce S. Eastwood, The power of diagrams: the place of the anonymous commentary in the development of Carolingian astronomy and cosmology.

However, this seems subsumed by the more detailed information in his book. There’s also an essay with a good discussion about Carolingian manuscripts of De nuptiis, especially the one called VLF 48 that I showed you, which may be the earliest:

- Mariken Teeuwen, Writing between the lines: reflections of a scholarly debate in a Carolingian commentary tradition.

For the full text of Copernicus’ book, translated into English, go here.

Re: Martianus Capella

Thanks, John.

Fascinating!

Demian