Shulman’s Practical Type Theory for Symmetric Monoidal Categories

Posted by Emily Riehl

guest post by Nuiok Dicaire and Paul Lessard

Many well-known type theories, Martin-Löf dependent type theory or linear type theory for example, were developed as syntactic treatments of particular forms of reasoning. Constructive mathematical reasoning in the case of Martin-Löf type theory and resource dependent computation in the case of linear type theory. It is after the fact that these type theories provide convenient means to reason about locally Cartesian closed categories or -autonomous ones. In this post, a long overdue part of the Applied Category Theory Adjoint School (2020!?), we will discuss a then recent paper by Mike Shulman, A Practical Type Theory for Symmetric Monoidal Categories, where the author reverses this approach. Shulman starts with symmetric monoidal categories as the intended semantics and then (reverse)-engineers a syntax in which it is practical to reason about such categories.

Which properties of a type theory (for symmetric monoidal categories) make it practical? Shulman, synthesizing various observations, settles on a few basic tenets to guide the invention of the syntax and its interpretation into symmetric monoidal categories. We reduce these further to the conditions that the type theory be: (1) intuitive, (2) concise, and (3) complete.

Intuitive. First, a practical type theory should permit us to leverage our intuition for reasoning about “sets with elements”. What this means in practice is that we require a “natural deduction style” type theory, in which contexts look and feel like choosing elements, and typing judgements look and feel like functions of sets. Moreover, we also require an internal-language/term-model relationship with symmetric monoidal categories which provide correspondences:

Concise. When stripped of the philosophical premises of what terms, types, judgements etc. are >, the rules of a type theory can be seen to generate its derivable judgments. It is therefore desirable that the translation between symmetric monoidal categories and the rules of their associated type theories proceed by way of the most concise combinatorial description of symmetric monoidal categories possible.

Complete. Lastly we ask that, given a presentation for a symmetric monoidal category, the type theory we get therefrom should be complete. By this, we mean that a proposition should hold in a particular symmetric monoidal category if and only if it is derivable as a judgment in the associated type theory.

Symmetric Monoidal Categories and Presentations of s

While it is well-known that every symmetric monoidal category is equivalent to a symmetric strict monoidal category, it is probably less well-known that every symmetric strict monoidal category is equivalent to a .

Definition. A , , consists of a set of generating objects and a symmetric strict monoidal category whose underlying monoid of objects is the free monoid on the set .

This is not however too hard to see: the equivalence between s and symmetric monoidal categories simply replaces every equality of objects with an isomorphism , thereby rendering the monoidal product to be free. We will develop what we mean by presentation over the course of a few examples. In doing so we hope to give the reader a better sense for s.

Example. Given a set , let be the free permutative category on . This is a symmetric monoidal category whose monoid of objects is the monoid of lists drawn from the set and whose morphisms are given by the expression

(where by we mean the reorganization of the list according to the permutation ). For every set , is a .

Example. For a more complicated example, let be a set and let

be a set of triples comprised of names and pairs of lists valued in . Let denote the free symmetric monoidal category generated by together with additional arrows for each . Then is also a .

Importantly, this second example is very nearly general - every admits a bijective-on-objects and full, but not in general faithful, functor from some of the form .

Example. Let and be as in the previous example and let

be a set of pairs of morphisms in the . Let be the quotient of the symmetric monoidal category by the congruence generated by .

This last example is fully general. Every , hence every symmetric monoidal category, is equivalent to a of the form .

Remark. If (generalized) computads are familiar, you may notice that our three examples here are free s on , , and -computads.

From Presentations to Type Theories

It is from these presentations of s that we will build type theories for the symmetric monoidal categories . Indeed, reading as “gives rise to”, we will see:

Contexts

The contexts (usually denoted , etc.) of the type theory are lists

of typed variables, where the are elements of the set . It’s not hard to see that, up to the names of variables, contexts are in bijection with .

Typing Judgments

As promised, typing judgments correspond to morphisms in . Here are some examples of morphisms and their corresponding judgements:

The rules from which these judgments may be derived correspond, roughly speaking, to applying a tensor product of generating morphisms in composed with a braiding - something along the lines of:

in which:

- is a context, and is a (list of) type(s);

- are terms of types respectively;

- the through are generating arrows in the set ; and

- is the avatar in of some permutation.

Now, it is rather clear that we are hiding something - the gory details of the rules from which the typing judgments are derived (the so-called identity and generator rules in Shulman’s paper). However, the reader should rest assured that not only are the details not that onerous, but the more naive structural rules corresponding to tensoring, composition, and braiding are admissible. In practical terms, this means that one is simply free to work with these more intuitive rules.

Equality Judgments

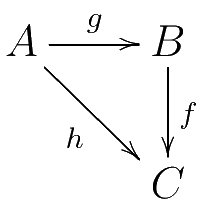

Equality judgments, for example something of the form which in categorical terms corresponds to a commuting diagram

are similarly derived from rules coming from the set . We will be more explicit later on within the context of an example.

How do Symmetric Monoidal Categories fit into all this?

Until this point it is not actually terribly clear what makes this type theory specifically adapted to symmetric monoidal categories as opposed to Cartesian monoidal categories. After all, we have written contexts as lists precisely as we would write contexts in a Cartesian type theory.

Although we may not always think about it, we write contexts in Cartesian type theories as lists of typed variables because of the universal property of the product - a universal property characterized in terms of projection maps. Indeed, in a Cartesian type theory, a list of typed terms can be recovered from the list of their projections. This is not the case for arbitrary symmetric monoidal products; in general there are no projection maps. And, even when there are maps with the correct domain and codomain, there is no guarantee that they have a similar computation rule (the type theoretic avatar of a universal property).

To illustrate this in a mathematical context, consider a pair of vector spaces and . Any element of the Cartesian product of and is uniquely specified by the pair of elements and - . However, elements of the tensor product need not be simple tensors of the form and instead are generally linear combinations of simple tensors.

Provided we are careful however - meaning we do not perform any “illegal moves” in a sense we will make clear - we can still use lists. This is what Shulman does in adapting Sweedler’s notation. Consider a general element

In Sweedler’s notation this is written as with the summation, indices, and tensor symbols all dropped. Provided we make sure that any expression in which appears is linear in both variables, this seeming recklessness introduces no errors.

To see how this plays out, suppose that we have a morphism with domain and co-domain being the tensor product . In Shulman’s adaptation of Sweedler’s notation this corresponds to the judgment:

Importantly, our typing rules will never derive the judgment and we will only be able to derive if we have in and more, unless specifies that acts like a projection, is but a name.

Since this type theory allows us to pretend, in a sense, that types are “sets with elements”, the symmetric monoidal aspect of the type theory can be moralized as:

- terms of product types are not-necessarily-decomposable tuples;

whereas in a Cartesian “sets with elements” style type theory:

- terms of product types are decomposable tuples.

Remark. Taking a hint from the bicategorical playbook can give us a more geometric picture of the difference between an indecomposable tuple and a decomposable one. Since every symmetric monoidal category is also a bicategory with a single object, a typed term, usually a -cell, also corresponds to -cells between (directed) loops. In this vein we may think of an indecomposable tuple as an -sphere in whereas a decomposable one, say , corresponds to a torus (of some dimension) in .

Example: The Free Dual Pair

Having sketched the basics of Shulman’s and how a presentation for a specifies the rules of for that , we may now attend to an important and illuminating example. We will develop the practical type theory of the free dual pair.

Recall that a dual pair in a symmetric monoidal category abstracts the relationship

between a vector space and its dual, .

Definition. A dual pair in a symmetric monoidal category is comprised of:

- a pair of objects and of ;

- a morphism ; and

- a morphism

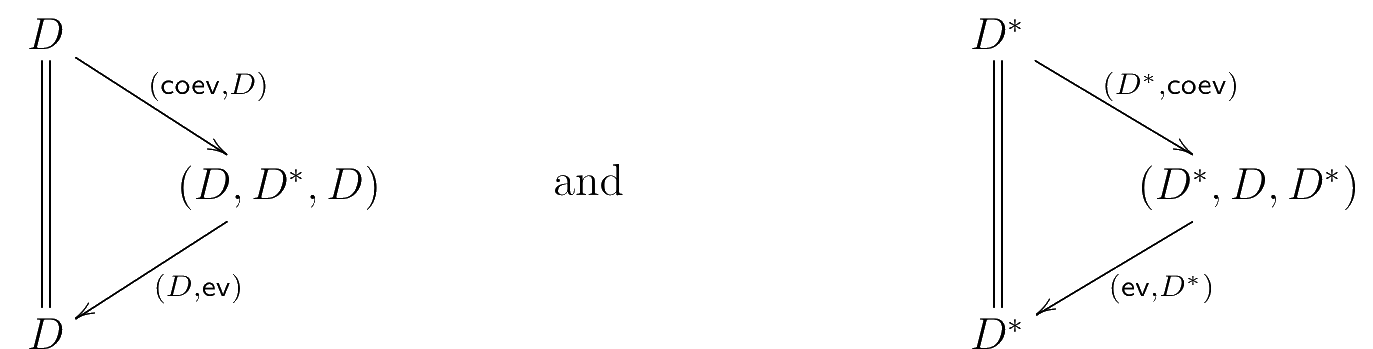

satisfying the triangle identities:

This data suggests a presentation for a , in particular the free dual pair. We set:

- ;

- ; and

The type theory of the free dual pair

We will now develop the rules of the type theory for the free dual pair from the data this presentation . While we have not bothered with them until now, Shulman’s practical type theory does include rules for term formation. In the case of the practical type theory for the free dual pair, the rules for the term judgment are few. We present a streamlined version of them:

The first rule is the usual variable rule which gives us the terms in which we may derive the typing judgments corresponding to identities. The second one gives us terms in which we may derive co-evaluation as a typing judgment. Finally, the last one gives us the terms in which we may derive evaluation as a typing judgment.

For the typing judgments, we have two (again slightly streamlined) rules:

- the so-called generator rule

(13)corresponds to applying a tensor product followed by a braiding and a shuffling of scalars. The tensor product is taken between generating scalar-valued functions (which can only be some number of copies of in our case) and the identity on some object, here . And,

- the so-called identity rule

(14)which corresponds to applying a braiding to the tensoring of some number of generating constants, here (which can only be some number of copies of ), and the identity on some object .

Remark. Here we are ignoring the notion consideration of “activeness”, a technical device introduced to rigidify the type theory into one with unique derivations of judgments by providing a canonical form for 1-cells. We also ignored the syntactic sugar of labels, which act like formal variables for the unit type.

Lastly, for the equality judgment we have axioms

and

together with enough rules so that acts as a congruence relative to all of the other rules.

Example. Consider the composition

which corresponds to the typing judgement

This typing judgement admits the following derivation

where:

- the first rule is an instance of the identity rule with premised generators and the braiding ; and

- the second rule is an instance of the identity rule with the typing judgement the consequent of the first rule and the additional hypothesis being the generator .

“Elements” of dual objects

We have now developed a type theory for the free dual pair which endows the dual objects and with a universal notion of element (that of -typed term and -typed term respectively). Since the notion of dual pair abstracted the instance of a pair of dual vector spaces, which in particular have actual elements, it behooves us to ask:

“to what extent is term of type like a vector (in )?”

The answer is both practical and electrifying (though perhaps the authors of this post are too easily electrified).

It’s easy enough to believe that the evaluation map

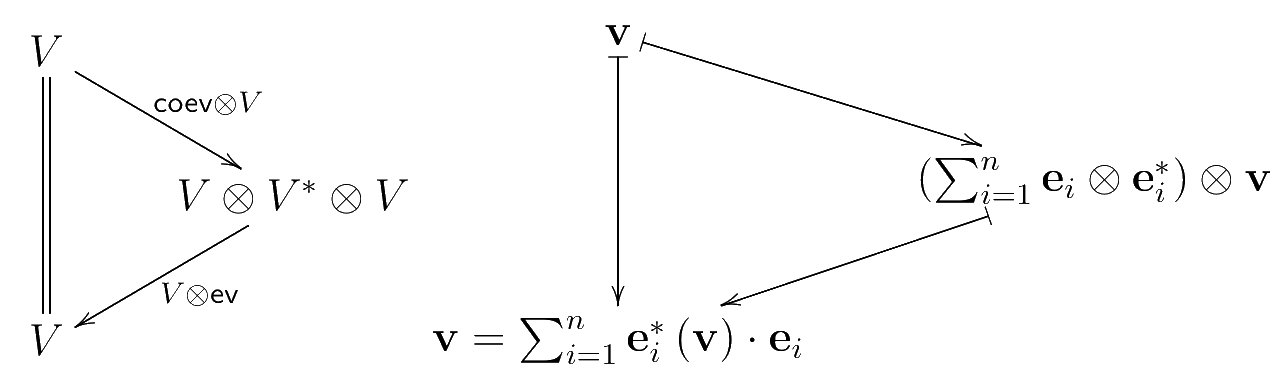

endows the terms of type , or for that matter, with a structure of scalar valued functions on the other. The triangle identities impose the unique determination of terms of type or in terms of their values as given by . Indeed consider that, for a finite dimensional vector space over a field , a basis for and a dual basis for give us an elegant way to write and the first triangle identity. We write

and see that

The observation for dual vector spaces

that the triangle identities hold is just the observation that a vector is precisely determined by its values: every vector is equal to the un-named vector

which is defined by taking the values at the dual vectors . As part of the definition of a dual pair in an arbitrary symmetric strict monoidal category then, the triangle identities imposes this as a relationship between and . But within type theory, this sort of relationship between an un-named function and its values is familiar, indeed it is something very much like -reduction.

To see this more clearly, let us make a pair of notational changes. In place of writing

we will denote infix by and write

Similarly, in place of writing

we will denote by the pair and write

With this choice of notation then, the equality judgment which corresponds to the first triangle identity is

Then, since is a congruence with respect to substitution (recall that we promised that the rules for the equality judgement were precisely those required for generating a congruence from a set of primitive relations), if we have, for some term , the term appearing in the scalars of a list of terms, then we may replace all instances of in the rest of the term with . While a mouthful, this is a sort of “-reduction for duality” allowing us to treat as a sort of -abstraction, as we suggested by the change in notation. Conceptually interesting in its own right, this observation also yields a one line proof for a familiar theorem, namely the cyclicity of the trace.

Example. Consider two dual pairs

in a symmetric strict monoidal category and a pair of maps

where denotes the permutation of entries of the list. Likewise the trace is the composition.

Using the notation introduced above it follows that as:

Where the judged equalities are applications of “-reduction for a duality”.

Re: Shulman’s Practical Type Theory for Symmetric Monoidal Categories

Interesting, thanks. I see in Mike’s paper he makes comparison with other notations (Sec. 1.10 and elsewhere), writing

Do you have a sense of when this type theory will display its advantages?