Octonions and the Standard Model (Part 9)

Posted by John Baez

The Riemann sphere leads a double life in physics. On the one hand it’s the set of states of a complex qubit. In this guise, physicists call it the ‘Bloch sphere’. On the other hand it’s the set of directions in which you can look when you’re an inhabitant of 4d Minkowski spacetime — as we all are. In this guise, it’s called the ‘celestial sphere’ . But these two roles are deeply connected! In 4d spacetime a Weyl spinor is described by a complex qubit: that is, a unit vector in . A state — that is, a unit vector modulo phase — simply says which way the spinor is spinning. Its spin can point in any direction, and these directions are points in the celestial sphere.

Last time I started explaining how to generalize some of these ideas from to what I’m really interested in, . Again this has two roles. On the one hand it’s the set of states of an octonionic qutrit. On the other hand it’s the heavenly sphere in a 27-dimensional spacetime modeled on the exceptional Jordan algebra. This is a funny spacetime where the lightcone is described not by the usual sort of quadratic equation like

but instead by a cubic equation.

It’ll be easy for me to get lost in the pleasures of this geometry. But I have a concrete goal in mind. The symmetries of form the group , and I’m trying to use this to understand a fact about . Namely, this Lie group has four Lie subgroups:

- the double cover of the Lorentz group in 10 dimensions

- translations in right-handed spinor directions

- translations in left-handed spinor directions

- ‘dilations’ (rescalings)

and these give Lie subalgebras whose direct sum, as vector spaces, is all of :

I proved these facts back in Part 7, but now I’m trying to understand them better. The duality between points and lines in projective plane geometry turns out to be the key!

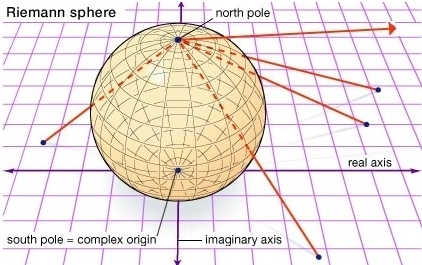

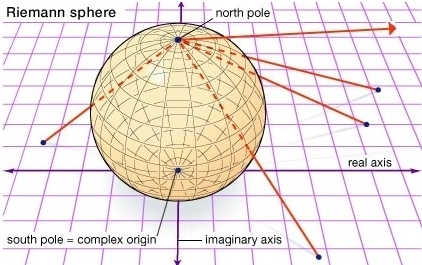

Recall the story from last time. The Riemann sphere consists of a copy of centered at together with a point at infinity, or ‘north pole’:

You can think of the sphere here as your eyeball, with the north pole being your optic nerve. The complex numbers are like a movie screen. Light streaming in from the movie screen hits your eyeball, and each point on your eyeball gets hit… except your optic nerve.

So, consists of all points of except . But there is also an ‘antipodal’ copy of consisting of all the points in except . Imagine another plane tangent to the north pole of the sphere in the picture above, and you’ll get what I mean. Conformal inversion, the map , gives a bijection between these two copies of .

This picture lets us describe four subgroups of the group of conformal transformations of the Riemann sphere:

- rotations of the sphere that fix the points and

- translations of the copy of containing : these fix the point

- translations of the copy of containing : these fix the point

- dilations that fix the points and .

The group of conformal transformations of the Riemann sphere is , and as described last time, it’s isomorphic to the connected Lorentz group .

Thus, these four subgroups give four Lie subalgebras of . And the cool part is that they add up to the whole thing:

as vector spaces. As a quick sanity check, note that the dimensions add up correctly:

since the dimension of is .

We now want to modify this story, replacing by . This involves two changes. We need to replace with . But the bigger change is to replace 1 by 2 — that is, replace a projective line with a projective plane.

From to

First let me quickly indicate what happens if we just replace with . There’s a space , which is an 8-sphere just as is a 2-sphere. When you give this 8-sphere its round metric it has a group of conformal transformations. This group is isomorphic to , the identity component of the Lorentz group of 10d Minkowski spacetime. But this group is also isomorphic to . Since the octonions are nonassociative, we need to work a bit to define . I did it one way here:

but you can see another approach here:

• Tevian Dray and Corinne A. Manogue, Octonionic Cayley spinors and , Section 2: the Lorentz group.

This paper is also worth looking at for the story about .

You can think of as a copy of together with a point at infinity. But there’s also an ‘antipodal’ copy of sitting in , centered at the point at infinity. These two copies of are related by conformal inversion:

All this is just like the complex case. If you’re a mathematician, you can visualize it by looking at this picture:

and imagining that both the 2-dimensional surfaces are 8-dimensional.

And just like in the complex case, we can see four subgroups of , or in other words the identity component of the Lorentz group , which acts as conformal transformations of :

- rotations of the sphere that fix the points and

- translations of the copy of containing : these fix the point

- translations of the copy of containing : these fix the point

- dilations of the copy of containing : these fix the points and , and also act as dilations of the copy of containing

These four subgroups give four Lie subalgebras of that add up to the whole thing:

As a quick check, note that the dimensions add up correctly:

since the dimension of is while that of is .

From to

Now let’s do something harder: replacing the projective line by the projective plane . The big difference is that while a projective line is just an ordinary line together with a point at infinity, a projective plane is an ordinary plane together with a line at infinity (which is a projective line). We used inversion to switch between two copies of sitting : one centered at and one centered at . To copy this trick for , we need to also use the duality between points and lines — a special feature of projective plane geometry.

Projective planes are a wonderful distillation of some old thoughts in axiomatic geometry. You’ve got a set of ‘points’, a set of ‘lines’, and a relation saying when a point ‘lies on a line’. You’ve got two axioms:

- any two distinct points lie on a unique line.

- any two distinct lines have a unique point lying on both of them.

These axioms are self-dual: for any projective plane there’s a dual projective plane such that points of are lines of and vice versa, and the ‘lies on’ relation is reversed! So we’re in a situation that really takes advantage of Hilbert’s remark on the arbitrariness of names in formal mathematics:

One must be able to say at all times — instead of ‘points’, ‘straight lines’, and ‘planes’ — ‘tables’, ‘chairs’, and ‘beer mugs’.

In projective plane geometry, instead of points and lines, one can say ‘lines’ and ‘points’, and all the theorems are still true!

Here’s how you get a projective plane from a field . You take a 3-dimensional vector space over . You define ‘points’ to be 1-dimensional subspaces of , and ‘lines’ to be the 2-dimensional subspaces of , and you say a point ‘lies on’ a line iff . The resulting projective plane is called the projectivization of , or .

What if we replace the vector space with its dual ? I’ll let you check: a point in corresponds to a line in , and vice versa, and the ‘lies on’ relation is reversed. So we have a natural isomorphism

where the dual at right is the dual for projective planes. Of course every finite-dimensional vector space is isomorphic to its dual, so we also have and thus . But these are not natural isomorphisms.

Now let’s take our field to be , and take .

We get a projective plane , but also a dual projective plane : points in one are lines in the other. consists of together with a line at infinity, say . Right in the middle of is the origin, . Since it’s a point let’s call it . So:

But the point in corresponds to a line in ! If we remove this line we’re left with a copy of — do you see why? And is sitting inside this . So:

In short, the situation is wonderfully symmetrical.

Now, the group acts as linear transformations of both and its dual. These are non-isomorphic representations of , which is why I’m being so careful to distinguish them. We get actions of on the projective plane and on the dual projective plane . And these let us describe four subgroups of :

- transformations in : these fix and , and act linearly on and

- translations of the copy of containing : these fix

- translations of the copy of containing : these fix

- ‘complex dilations’, i.e. transformations of of the form for : these also act as complex dilations of , and they fix both and

By analogy with what we’ve seen so far, we could hope for an isomorphism of vector spaces

And in fact it’s true! I won’t prove it here, but it’s not hard. Each of the four pieces at right at right is a Lie subalgebra of , but they don’t all commute with each other so this is not an isomorphism of Lie algebras.

As a check we can see if the dimensions add up correctly… and they do!

We can also think of this in terms of groups and group representations. is the double cover of the connected Lorentz group , and and are its right-handed and left-handed spinor representations — called Weyl spinors. So, in some sense we can chop into four parts:

- the double cover of the Lorentz group in 4 dimensions

- translations in left-handed spinor directions

- translations in right-handed spinor directions

- complex dilations.

But this is easier to make rigorous at the Lie algebra level, where is the direct sum of four subspaces that happen to be Lie subalgebras:

- the Lorentz Lie algebra

- right-handed Weyl spinors:

- left-handed Weyl spinors:

- complex scalars:

From to

The octonions are not a field, but the story I just told generalizes from to .

The projective plane has a dual, . Points in are lines in the dual, and vice versa. consists of together with a line at infinity, say . Right in the middle of is the origin, which we’ll call . So:

But the point in corresponds to a line in . If we remove this line from we’re left with a copy of , and we get

The group of symmetries (technically ‘collineations’) of the projective plane is our friend . This also acts on the dual projective plane. Using this fact we get four subgroups of , almost like in the complex case:

- transformations in : these fix and , and act linearly on and

- translations of the copy of containing : these fix

- translations of the copy of containing : these fix

- dilations, i.e. transformations of of the form for : these also act as dilations of , and they fix both and .

Following the pattern, we could hope for that the Lie algebras of these subgroups add up to give the whole Lie algebra of . And it’s true!

Again, each of of the four pieces at right is a Lie subalgebra of , but they don’t all commute with each other so this is not an isomorphism of Lie algebras.

As a sanity check we can see if the dimensions add up correctly. In fact I already did this back in Part 7. So, its Lie algebra has dimension , and the sum goes like this:

And we saw another way to think about this stuff. is the double cover of the connected Lorentz group , better known as . The spaces and are the right-handed and left-handed spinor representations of , called Majorana–Weyl spinors. So, what we’re doing is breaking the Lie algebra into four parts, that happen to be Lie subalgebras:

- the Lorentz Lie algebra

- right-handed Majorana–Weyl spinors:

- right-handed Majorana–Weyl spinors:

- scalars:

Okay, I hope the picture is reasonably clear by now — though there is still work required to check everything, which I haven’t done here. If I were being more systematic I’d generalize this story to the projective spaces for all normed division algebras — for all when is associative, but only when . In higher dimensions there’s a duality between points and -dimensional projective subspaces. But the story is most interesting to me when it involves the coincidences

And right now I’m just interested in the complex and octonionic cases, which are linked by these inclusions:

with being a nickname for .

- Part 1. How to define octonion multiplication using complex scalars and vectors, much as quaternion multiplication can be defined using real scalars and vectors. This description requires singling out a specific unit imaginary octonion, and it shows that octonion multiplication is invariant under .

- Part 2. A more polished way to think about octonion multiplication in terms of complex scalars and vectors, and a similar-looking way to describe it using the cross product in 7 dimensions.

- Part 3. How a lepton and a quark fit together into an octonion — at least if we only consider them as representations of , the gauge group of the strong force. Proof that the symmetries of the octonions fixing an imaginary octonion form precisely the group .

- Part 4. Introducing the exceptional Jordan algebra : the self-adjoint octonionic matrices. A result of Dubois-Violette and Todorov: the symmetries of the exceptional Jordan algebra preserving their splitting into complex scalar and vector parts and preserving a copy of the adjoint octonionic matrices form precisely the Standard Model gauge group.

- Part 5. How to think of self-adjoint octonionic matrices as vectors in 10d Minkowski spacetime, and pairs of octonions as left- or right-handed spinors.

- Part 6. The linear transformations of the exceptional Jordan algebra that preserve the determinant form the exceptional Lie group . How to compute this determinant in terms of 10-dimensional spacetime geometry: that is, scalars, vectors and left-handed spinors in 10d Minkowski spacetime.

- Part 7. How to describe the Lie group using 10-dimensional spacetime geometry. This group is built from the double cover of the Lorentz group, left-handed and right-handed spinors, and scalars in 10d Minkowski spacetime.

- Part 8. A geometrical way to see how is connected to 10d spacetime, based on the octonionic projective plane.

- Part 9. Duality in projective plane geometry, and how it lets us break the Lie group into the Lorentz group, left-handed and right-handed spinors, and scalars in 10d Minkowski spacetime.

- Part 10. Jordan algebras, their symmetry groups, their invariant structures — and how they connect quantum mechanics, special relativity and projective geometry.

- Part 11. Particle physics on the spacetime given by the exceptional Jordan algebra: a summary of work with Greg Egan and John Huerta.

- Part 12. The bioctonionic projective plane and its connections to algebra, geometry and physics.

Re: Octonions and the Standard Model (Part 9)

Typo: missing parenthesis after .